New Zealand’s unemployment rate recently fell to an incredibly low 3.4% in September. This means that only 3 out of every 100 people who are keen to work have been unable to find a job.

Unemployment is now sitting at a record low rate, equal only with another 3.4% result recorded way back in December 2007.

Unemployment is prone to measurement error and could bounce around again next quarter. But looking through such ‘noise’ the real questions are – do we trust the general tenor of this recent unemployment result and, if so, what does it mean?

Labour market is tight no matter which way you dress it

Some commentators have been quick to dismiss the unemployment rate as being unduly skewed by Auckland’s prolonged lockdown. These commentators are saying that unemployment has only fallen because we have people locked down at home who haven’t been able to look for work. Technically these people don’t have a job, but because they can’t physically search for work they haven’t been officially captured by Statistics New Zealand as unemployed.

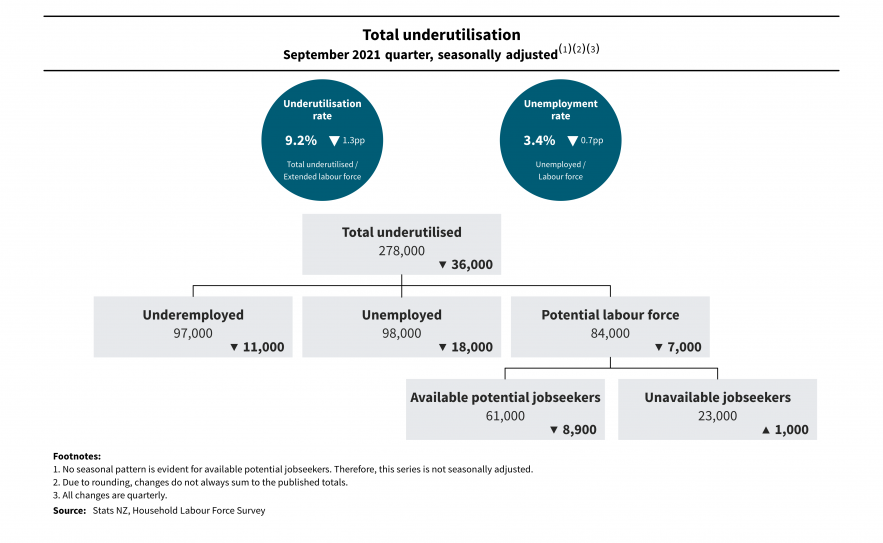

At first brush, this argument holds some merit, particularly when we see other measures of spare capacity in the labour market, such as the underutilisation rate sitting much higher at 9.2%. In addition to people who are unemployed, the underutilisation rate includes people underemployed (those who are employed part-time yet want and are available for more work) and people who want jobs but are either unavailable to work or not actively seeking work (the potential labour force).

But even then, there are limits to this argument as underutilisation in September was 1.3 percentage points lower than its 10.5% result from June, and a full 3.9 percentage points lower than a year earlier.

The recent decline in underutilisation has been broad-based across all its different parts. In other words, underutilisation can’t just be pinned to the narrow grouping of people who don’t have a job and can’t get one because public health restrictions have limited their ability to get out and about.

The following diagram shows changes in underutilisation by its different sub-parts.

Of the 36,000 people who were underutilised in the September quarter, the diagram shows that:

- 11,000 of this decline was because of fewer people being underemployed. These are people who have a job but want to work more hours. This decline is consistent with jobs growth data which showed that seasonally adjusted employment growth in the September quarter for full-time employees was 2.3%, while part time employment slipped slightly.

- 18,000 of the decline was because of fewer unemployed (people who want and are available to work and are actively seeking it).

- 7,000 of the decline was because of better utilisation of the potential labour force – comprising 8,900 fewer available potential jobseekers (people who want and are available to work but have not actively sought work), and offset by a small 1,000 person increase to unavailable jobseekers (people who have been looking for a job but are unable to start immediately).

The small increase to unavailable jobseekers is perhaps the only measure within underutilisation that can be directly pinned to lockdown restrictions because these are people who face some kind of impediment to their immediate start, despite actively looking for work. Nevertheless, a 1,000 person increase to this category pails in comparison to the overall magnitude and broad-based nature of falls to other aspects of underutilisation.

Participation is at a record high

We are now in a situation where the working age population is being utilised like never before. Over the year to September 2021, 115,100 more people were employed, to reach a total of 2,819,200, which lifted the participation rate for the working age population to a record 71.2%.

The increase to employment is pleasingly broad-based across genders, demographics, and ethnicities. The following changes were seen in each subgroup over the year to September 2021:

- Sex

- 78,000 more women in employment, to reach 1,343,300.

- 37,100 more men in employment, to reach 1,475,900.

- Age

- 30,100 more 15–29-year-olds in employment.

- 37,400 more 30–44-year-olds in employment.

- 17,600 more 45–59-year-olds.

- 29,900 more employed people aged 60 and above.

- Ethnicity

- 119,100 more people who identified as European in employment, to 2,010,700.

- 29,900 more Māori in employment, to 387,800.

Wages are rising fast, but not nearly enough

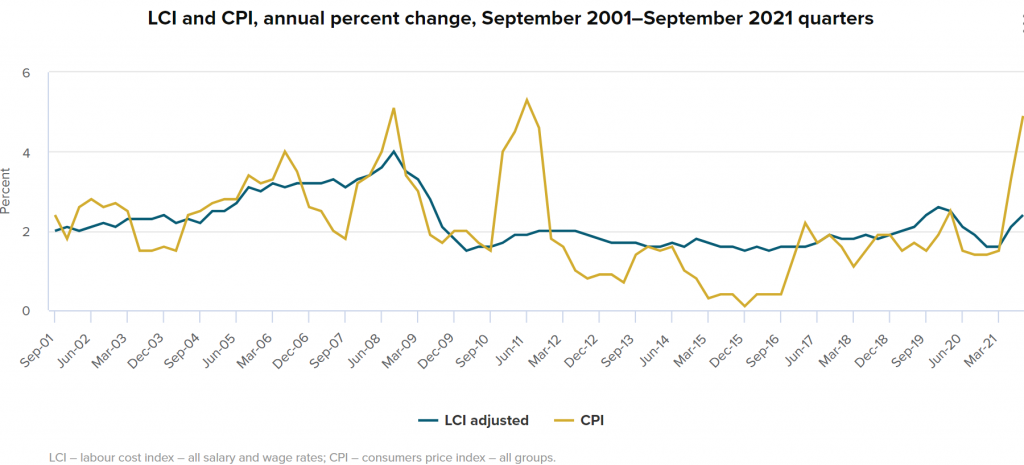

With the labour market having tightened, wage growth has begun to pick up to levels last seen more than a decade ago. Rising wages are no surprise given businesses are demanding workers, but the pool of those to entice into job opportunities is relatively slim and so there is a need to pay more to attract and retain workers.

The labour cost index (LCI), which strips out the effects of job creep to give a consistent measure of how much it costs to find workers, shows that there was a 2.4% increase in labour costs over the past year. Within this increase there was a 2.5% lift in private sector wages, while there was a 1.9% increase in public sector wages.

By comparison, labour costs have been increasing by an average of 1.5% to 2.0%pa over the past decade. It was only before the Global Financial Crisis that we saw consistently higher wage growth.

Nevertheless, recent wage increases are not nearly enough to counteract rising costs of living across the country. In the September 2021 quarter, annual CPI inflation was 4.9%.

Given these cost of living pressures, at a time when the labour market is tight, expect employees to get tougher in their wage bargaining next year. Employees may begin to feel emboldened. The reality is that the power balance has shifted to the employee and employers will need to sharpen their pencil if they are to attract and retain workers in this competitive market. Border reopenings may help in some industries, but you would be a fool of a businessperson to not put your focus on making sure your employment offering is compelling.